Prologue: Neighbourhood

You don’t look out late at night as often as you should. You miss all sorts of things. Like a pair of legs emerging from the living room window of a small terraced house, a girl dropping down onto the pavement with trainers under her nightdress. Another girl escaping through a back door, two flights down from her sleeping parents, the night pouring into the house as she steps out into the garden in pyjamas and bare feet. A third girl sliding open the patio doors. A fourth and fifth leaving by the front porch, as casually as leaving for school.

Then ten feet tip-tapping through the dreaming, fidgeting neighbourhood, ten feet pat-patting along the bluey streets. Crossing the main road with muscle-memory caution, looking left and right before hurrying across the empty space, loose hair bouncing. Quick, quiet bodies shuffling past shuttered and darkened shop windows, watched by a dead-eyed mannequin that has been peering over the same Closing Down sign for most of a year. Onto the Green beside the shops, size three, four and five feet landing on damp and weary grass, treading to the darkest corner where the grass is frost-crunchy and the ground dips in a sunken circle. Atishoo, atishoo, we all fall down laughing. Dirty soles and grassy-kneed nightwear. Under milky light, five girls sit and sprawl, listing all the kinds of dark there are.

“Doom dark”, says Asha, plaiting dozing daisies into Mina’s hair.

“Dark behind the stars,” says Jodie, ripping a blade of grass in two.

“Dark in the heart cracks,” says Kelly.

“The dark in the crow’s voice,” says Mina.

“Distant dark,” whispers Diana, warming the words in her mouth.

This all came later, but it’s how I most like to remember them.

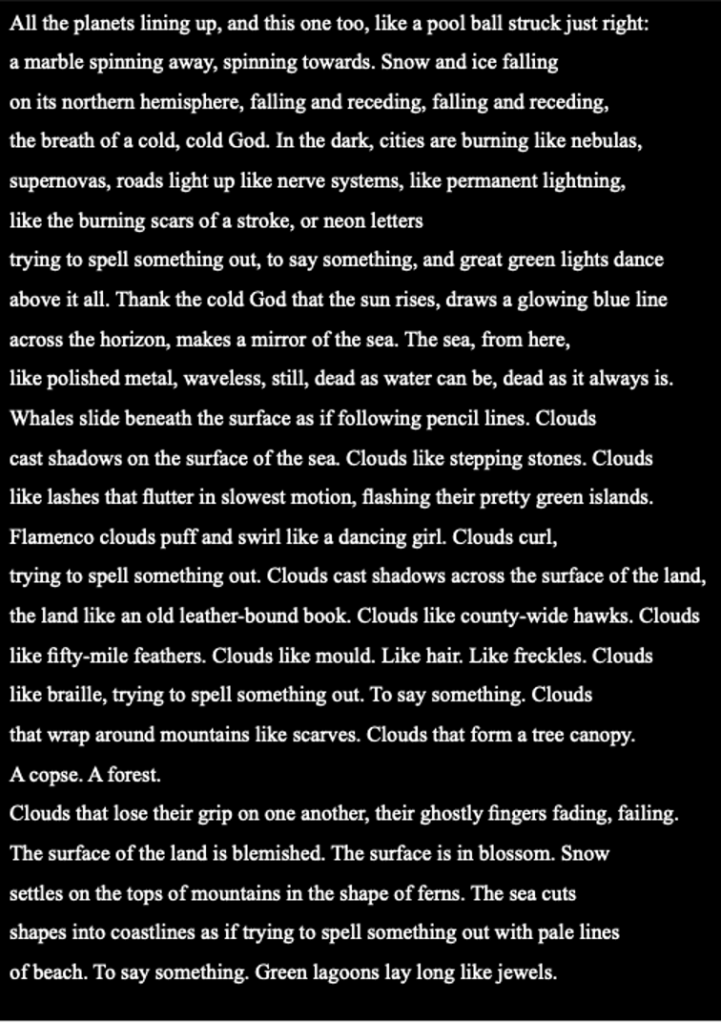

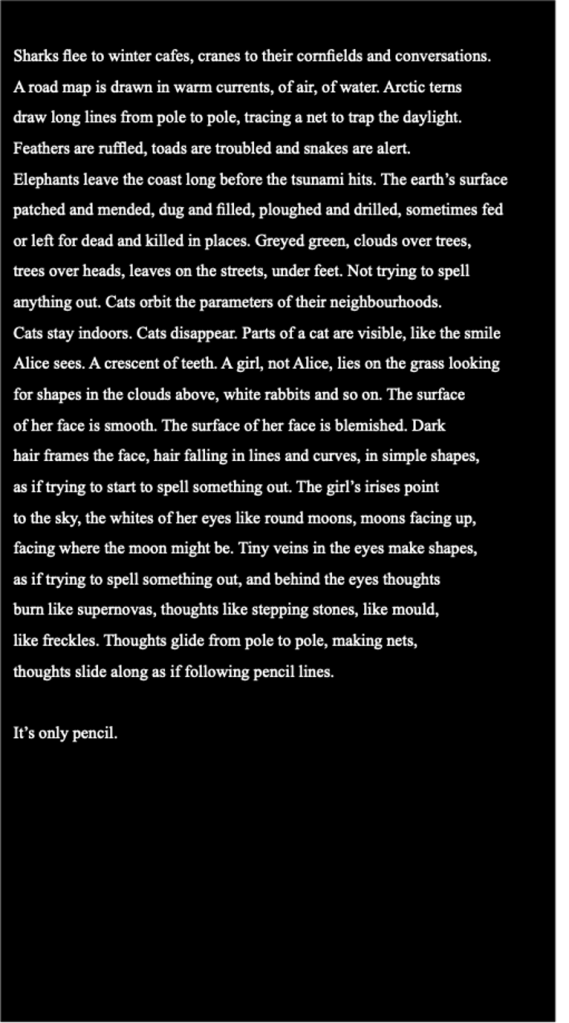

I’ll try to make it easy, seeing as how your eyes are so small. These girls lived in a sort of star-shaped suburb in the north of England; hill-hampered, wind-blown, dry. People who had lived there a long time liked to call it a village, though many of them felt a little disingenuous when they did so. Ethnically speaking it was, still is, as white as my face in most places but black as my back here and there. Economically speaking some residents would peer down from high ridges whilst others languished in dark craters. If I wasn’t attracted to everywhere on Earth I would say something almost witty like I can’t imagine what attracted me to this place.

The girls all lived in the uppermost triangle of this star-shaped place, and at the top of the triangle sat the comprehensive school they all attended. A road drew a line under the school, and below the line began two long streets which stretched like a pair of open legs all the way down to the centre of the star, those kind of long English streets where the style of the houses constantly changes, like a shelf of bric-a-brac; terraces, semis, all manner of variation in doors, windows and other apertures. The few trees on these streets unsettled the pavement and pushed parts of the curb into the road so that they stuck out here and there like fungus. Lamp posts boasted missing cat posters by day and bled yellow circles at night. At their bottom end, the streets met the road to town, or far away from town in the other direction. This road ran through the star’s nucleus, where there was an uninspiring stretch of grass known as The Green, which perhaps explains the whole village thing, along with a small playground and a modest shopping crescent. The shops were not very good shops – it was not yet that kind of suburb.

This tall triangle, from the school to the Green, should be manageable for your pinprick eyes, should help you picture the neighbourhood as it was then, though on reflection perhaps neighbourhood is not the best word. A neighbourhood, now I think about it, is generally less cut off and isolated from its surroundings than, say, a solar system (though who knows what Neptune thinks), so that a girl living near the top of the northernmost star-point might have described hers entirely differently to a girl who lived closer to the star’s centre. It seems a neighbourhood is more difficult to describe than the whole of which it is a part. Anyway, that doesn’t matter.

What matters is that you don’t look up as often as you should. It was the same in this neighbourhood as everywhere else. You’d have missed all kinds of things;the well-fed bats politely applauding a particularly pleasant evening’s end, the exact same cloud that visited the Green on the same April day each year,and of course all the gifts that I sent down daily and nightly. I am nothing if not generous, gently dropping my gifts upon you all throughout the centuries. I give myself up so often. It’s difficult for you of course, with such sweet little onion eyes, to distinguish during a storm which of the hailstones are really hailstones and which are little melting moons, but if you could just stop blinking so much you might notice a crescent floating down on a mild afternoon, barbed on a feather, or realise that you aren’t stepping on chewing gum this time, but a friendly gibbous laid at your feet.

In this neighbourhood there wasn’t room for anything too grand; I’d never cut deep a canyon or laid as a lake bed, as in other places. I’d lately landed as a balled-up tissue beside a sorrowful sniffler, half-drowned myself as a soap bubble in a window-cleaner’s bucket, slotted into a stack of empty plates on a kitchen sideboard, and laid as more chewing gum to be stepped on. The larger houses in the neighbourhood, the ones with drives and decorative statues, had generally acquired more of me than the smaller homes, as I mixed my little selves into gravel or nestled them amongst the curls of a sitting lion’s stony mane. And I watched. Peering from behind straggling clouds to see if anyone would take one up in their arms, these pieces of me. This is a story about someone who did. There have been many of course, and I could tell you about them, but this was a girl who almost matched me in my loneliness, and it was not so long ago.

I’ll have to step back into the dark, I suppose, try to show you what happened through other small eyes like your own, not like mine, but you’ll never be able to see what she was like, this girl, not really. If you had my sight, especially on a bright and plump day, you could see the hooks in her skin that kept the past dragging along behind her, and how she was small and thin because of all the love that had been pushed back inside, love rotting there like teeth or corroded into a thin grimy film that lined her every bone. You’d see how those bones buzzed a little when she hadn’t had enough water, which was often. You’d see the imaginary helmet she sometimes wore, and the pictures of good feelings she stuck to the inside of it; brasso and chamois leather, a frisbee across a blue autumn sky, drinking coke through a straw. You’d see how her stomach was a tombola barrel of lit dynamite sticks. But you can’t see any of that, with your wet little marble eyes.

Part One: Sea of Love

Moon, Landing

Miss Gaunt recalls

The boys at school called her ‘Princess’. Sometimes they pretended to run her over, crashing into her, or they would act like a distraught young prince and cry at her ‘Mammy, Mammy!’ Now and then one of the girls would join in and then Diana would ‘get nasty’, as Mrs Land would describe it. Mrs Land was always trying to help her.

Diana M. was a slight, bright girl. Talented, yes. Only, very sensitive, perhaps a touch too sensitive. She could lose her grip on herself and end up stumbling around in the dark, though she was usually fine during Miss Gaunt’s art lessons. On the day that Diana was late to Miss Gaunt’s class, after Mrs Land had called Diana’s left-leaning handwriting ‘improper’ and ‘precarious’, and the same day that something fell out of Diana’s art folder, Miss Gaunt, who was very tall, had seen Diana through the large windows that looked out onto the quad; Diana marching across the courtyard, entering the Art Block and the classroom, her eyes puffy. Along with half the class, Miss Gaunt had watched Diana drag her big folder from a shelf and throw it down onto a desk beside Mina T., then climb up onto a high stool and put her arms on top of the folder and bury her face so that it was completely hidden, her long dark ponytail tossed over towards the front of her head. Miss Gaunt, striding over, had asked Diana where she had been.

“Mrs Land,” came the muffled reply.

“Right, OK. Are you going to do some work?”

“Yes.”

“OK, good. Do you need a tissue?”

“No.”

“Take your coat off please.”

Miss Gaunt led a calm class. Colleagues were surely envious of the sweet diligence of her pupils during their time amongst the clay and paint. Her presence instilled tranquility in the room, an extension of sorts of the yoga classes she taught during the holidays, where she showed women how to quietly curl themselves into a variety of lovely shapes. A sense of flow, of serenity both inside and out, was important to Miss Gaunt, who wrapped her physical self in long shirts and bright scarves. Only her orange hair, cut sharply around the jawline, gave an edge to the teacher, who was not as emaciated as her name suggested; she was long but also broad and lean, a healthy flush in her cheeks.

Diana’s large art folder was not a thing of serenity. It was not like Mina’s neat plastic folder with its smart red handle. It was an awkward, battered cardboard thing with a grisly paisley pattern, and it bulged with dog-eared scraps of paper, its two long elastic strings struggling to keep it closed. Diana opened it and took out her work.

“This is so shit.”

Miss Gaunt had assured her that it was not, “And these are just studies, aren’t they? It’s not the final piece?” She had held up the large sheet of paper, smudged and fingerprinted at the corners, and she, Diana and Mina had peered at it. The paper was covered in drawings of Diana’s left hand, in different styles and colours, focusing on the lines of the palm. Miss Gaunt asked Diana to remind her how this fit with the assigned theme, and Diana’s eyes had filled with tears again, “So it doesn’t even fit with the theme?”

“That isn’t what I said,” Miss Gaunt had said, in her softest lullaby voice. “Talk me through it again. Maybe it will help you remember what you wanted to do in the first place.”

Diana, sighing, had explained: “It’s like, like when someone says you know something like the back of your hand. And I thought I probably wouldn’t know the back of my hand if someone showed it to me. So I thought I’d learn it. Except I did the other side of my hand. For the lines.”

“See? It absolutely fits with the theme. Such a good idea. Just keep going.”

“It does fit,” Mina agreed. She was drawing a huge ant in great detail. “Miss, do you like my thorax?”

Miss Gaunt was immensely proud of her pupils and their ever-giving imaginations, which often needed only the smallest nudge to go spinning off in marvellous directions. She loved the flexibility of their study, which she felt far exceeded the way other subjects were taught, even English, with all its wrong questions and right answers. She was satisfied that she had chosen the correct career path and felt she was in just the right place. She was sure her pupils appreciated how she trusted them with their own ideas, how she was not as proscriptive as, for instance, Mrs Land who, poor woman, must have been under so much pressure as both Head of English and Head of Year 9.

At the end of that day, the day Diana was late and something fell out of her art folder, the issue of Diana had come up in the staff room, and Miss Gaunt had suggested to Mrs Land that perhaps Diana hadn’t been sure if Mrs Land was really talking about her handwriting that morning, when she said it was ‘improper’ and ‘precarious’, that maybe there was more to the reason that Diana had burst into tears and been late for art. Mrs Land and Miss Gaunt discussed the issue of Diana, and Diana’s issues, further. Mrs Land informed Miss Gaunt that she had kindly offered to talk to Diana out of school hours, that she had said she would be available late on Saturday afternoon before the school concert, and hoped that Diana would take her up on it.

Mr Grant had chimed in to say that whilst he had talked about rivers and tributaries that afternoon, Diana had been drawing on her hand and he had had to tell her to stop it and pay attention. Mr Wiles the French teacher bemoaned that as usual nobody had been paying attention in his class, and that lists had instead been drawn up about who was the best looking and the worst looking, one list for the girls, one for the boys, and Mr Wiles had had to fetch the German teacher to help control the class.

Miss Gaunt knew how slowly the school’s heart must seem to beat for her pupils, extending interminably those forty-five minute pauses between pumps, til – at last – the bell would send pupils gushing from one classroom to another, or bleed them out into the quad for a while.

That day Diana had looked sad when the bell sounded the end of the art lesson, though Miss Gaunt knew that all she had done was draw over many of the lines on her actual palm with blue biro and talk to Mina about the X Files. Miss Gaunt watched without comment as Diana pushed her work carelessly back into her folder, then with heavy coat squeezed under an elbow and schoolbag over her shoulder she awkwardly threw the folder back onto its shelf; it was then that Miss Gaunt saw something start to slip from within the ugly thing; some creased pieces of paper with drawings on, and with one swift stride the tall teacher and her long and ringless fingers swooped into the right place in space and time, deftly saving the fluttering escapees before they reached the floor. A smile had spread across Miss Gaunt’s face as she returned to her full height, her eyes on the drawings. Her mouth opened to call Diana’s name, but Diana had already followed Mina into the vein of the corridor and was long gone. “Duh” had emerged from Miss Gaunt’s mouth anyway.

White Sharon

White Sharon went back years, absolute yonks, with Joan. She was just known as Sharon back in the day of course, the distinction had come later.

White Sharon is quite sure that it was that year, the year of the incident, that Diana stopped her habit of looking through Joan’s photo albums, which had pleased Joan because Diana never put them back properly. Joan had once told the social worker about Diana and the albums, using the word ‘unsettling’. Joan said she didn’t know why Diana liked looking at all those photos of people she didn’t know.

Most of the photos in the albums, which Joan liked to keep in chronological order on the bottom shelf near the TV, were taken before Diana was born. Before Diana existed. Long before Diana’s father left. Before her mother was gone. And her grandmother. Long before Diana came to live with Joan.

Diana’s favourite seemed to be the white one with the little gold star pattern. It creaked like an old door when it was opened. When is a door not a door? A photo album is a kind of door.

All the photos behind the door were imprisoned behind cellophane, presumably to protect the precious memories from greasy fingers, rather than to protect people from the images kept there. Joan’s mother and her half-sister eating chips at the seaside. Joan’s mother posing with a tiny monkey on a leash.

When she was younger, Diana used to ask the same questions about the same photos until one day when Joan had asked her to stop.

“Who’s this?” she would ask, pointing to a picture of Joan’s pregnant mother; she’s nineteen, stood against the brick wall of her own mother’s house, next to her half-sister. A black dog sits beside them, looking out of the frame.

“That’s my mum, with me in her belly, and my aunty Lil, and Sam. He used to guard my pram when I was asleep. But he died when I was still a baby.”

“How?”

“He went off to die in a field,” Joan would say. The first time she had added “that’s what they do,” something her own mother had told her, and Diana had adopted that line, so that later when Joan said “He went off to die in a field,” Diana would say “That’s what they do.”

Joan and White Sharon had laughed about Diana and the photo album. Joan showed White Sharon the photos. Joan had laughed about the dog.

“I always imagined him going to lie down and die in a field of wheat on a lovely summer’s day, but she’s got me thinking about it again and there were no bloody wheatfields round there. It was crap where we lived, he went off to die in a car park more like. Stuff they tell kids, eh.”

The social worker had told Joan that Diana’s mother had The Black Dog, among the other things. She said Diana would likely have it too as she got older, that these things tend to run in the family. Joan had told the social worker that her own mother was the same but that Joan herself had never had anything like that, so she wasn’t sure if she agreed about Diana having it when she got older.

The social worker said that Diana’s mother had talked to Diana about death, talked about it a lot. That she would tell Diana ‘I don’t want to die’. That she would take Diana to see the grave plot she had bought for herself, next to the stillborn son who would have been Diana’s half-brother. It was a double headstone and Diana’s mother’s side was blank. She says that Diana’s grandmother, the blind one, had also had The Black Dog and that she had had electric shock treatments.

Joan had said how things were different back then. She had told the social worker about her own grandmother, who didn’t know how babies were made until she’d had five kids of her own and the doctor explained it to her. She thought that’s just what happened when you were married.

The social worker said that Diana’s grandmother had told Diana that the shocks had melted her eyeballs, and that’s why they looked funny.

Joan said she’d had a horrible dream about Sam, the black dog in the photo, where she thought he was protecting her and tried to pull him around her like a fur coat, only it turned into some kind of shroud and she fell into a grave. White Sharon didn’t know why that had stuck in her memory; she didn’t normally remember other people’s dreams. Perhaps it was just because Joan hadn’t seemed her normal laid-back self, you know?

White Sharon didn’t tell Joan, at least not in so many words, but she found Diana to be a strange and sullen little thing at times, and thought there must be a chance that she was just like her mother.

On the last page of the white photo album with the gold stars, Diana would always study a photograph of Joan’s mother and her half-sister leaning on a barrier at the zoo, a giraffe striding into the background. Diana would always ask the same question:

“Joan, in a zoo are the barriers to protect the people, or the animals?”

Asha

Many years later, over breakfast, Asha told her husband that when she was still at school she woke up in her bed one morning with dirty feet and grass stains on her nightie. As she was telling him, she suddenly remembered that she had been on the Green at midnight that night long ago, with her sister Mina, poor thing, and some of the other girls from school and that a girl called Diana had given them all some stones out of a wooden jewellery box and she told them they were gifts from the Moon and when they had held the stones they had all fallen down in some kind of hypnotised stupor, and she couldn’t remember getting to the Green or getting home again and that sometimes she still thought about the things that had happened around that time and that maybe she should see a therapist. She was very upset.

When Asha went to see a therapist, she described for her the night she went to Diana’s house and saw Diana pull out one of her cat’s claws. Diana had made the claw into a pendant, Asha said, and Asha remembered Diana wearing it, like a crescent moon on a black string. Asha knew the pendant was real, but told her therapist that she was unsure whether her memory of Diana pulling the claw from the cat was real, even though it seemed like a real memory. The therapist said it didn’t matter whether it was a real memory or not.

Asha began to remember lots of things about Diana. She remembered how she hadn’t liked her. She was always making a fuss, crying about things, always trying to get attention. She was smug too; always top of the list of the prettiest girls in school and she would just smile and not say anything. She was a drama queen; one day when Asha and the other girls arrived to get ready for the school concert Diana was there, waiting outside the Music Block, and she was looking at Mrs Land like Mrs Land was supposed to do something, say something, and Mrs Land didn’t know why Diana was there and asked if Diana had come to help and Diana stormed off crying and we all laughed when she had gone, even Mrs Land.

But along with these memories were others, kinder ones. She remembered the small house Diana lived in with that woman, Joan, a white stucco house that seemed cold and dark on the outside in comparison to the house next door that was painted bright yellow. But it was warm inside, and Joan was nice. Joan wore soft jumpers and made jokes and hot chocolate. Yes, Asha remembered feeling close to Diana, for a time.

More memories rose up, like dreams, almost. From out of nowhere, Asha remembered a chant:

Upon a field of frozen stars

A goddess lay in her mother’s arms:

“All lightless day I’ve sailed to thee

from yon snow globe eternity”

Like sudden sisters in the womb

The egg was split, the doubled moon

Was whole and halved, was two and one

Was home at last, an end begun.

Asha didn’t know what it meant, didn’t know if she had ever known. The words felt dark to her, though there was something comforting about them at the same time.

Asha remembered how one night the Moon had broken in through the window and rolled around naked on the landing.

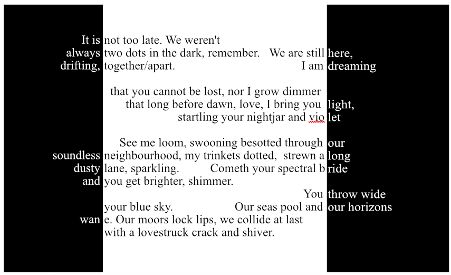

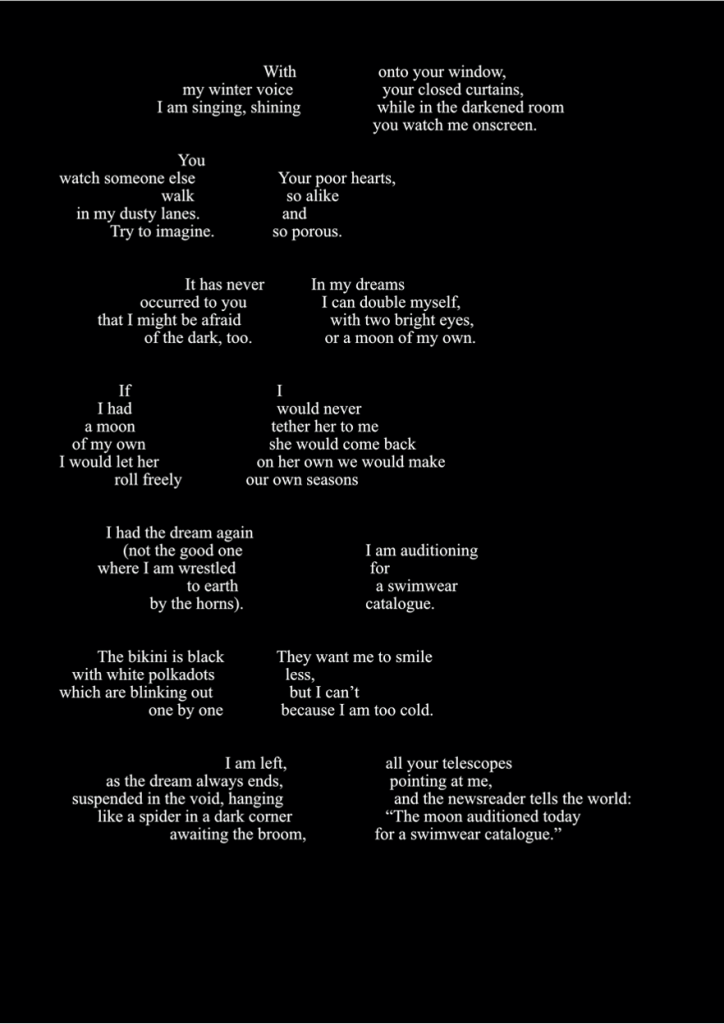

Part Two: You Get Brighter

Eye Rolls

Mrs Land

Yes, there had been a wave of problem behaviour that term, even prompting the Head to give a special assembly on the subject of role models. Mrs Land strongly supported this step, and even suggested a theme; Year 9 had been writing about the heavens in her English class and discussing various celestial characters and Mrs Land thought the Moon made a fine model of patience and calm, quietly listening, not speaking, as it rolled overhead. The Head however decided to avoid anything ‘flowery’ and instead began his address by reminding the pupils of the school’s ‘Pillars of Learning’.

The Pillars of Learning were one of the Head’s first contributions when he had taken on the role a few years previously, an idea inspired by the building itself, and which he said had come to him when he arrived on his first day. The school sat on the flat of a hill, so that on entering the main gates the tarmac sloped upwards towards the entrance; large double doors reached by six steps. At the bottom of the steps stood four large cement columns, two either side, each topped with a colossal cement ball. The columns were a rather obvious attempt to make the school look older and grander than it really was, but Mrs Land, who had taught here for thirty-odd years, liked them very much. The new Head had decided to use these columns to represent what he had then drawn up as the school’s new Mission Statement, and had posters designed and put up throughout the school showing a cartoonish image of the columns, brightly coloured and with each ball atop bearing in flourishing script the terms Working Together, Nurturing Excellence, Building Futures and Broadening Horizons. It was these values that the Head sought to reinforce in his assembly.

What has always bothered Mrs Land most about that assembly was that she had been unable to spot Diana M., Asha and Mina T., Jodie H. or Kelly D. in the throng of blank faces pointing up at the Head that day, though they did somehow reappear at the end, trickling out of the gym along with everyone else. It was that particular group of girls that had made the assembly necessary, with concern growing that their recent behaviour could become infectious.

It all seemed to revolve around Diana, who had suddenly become quite the centre of attention. Diana – unstable, short-tempered, over-sensitive – had always needed additional support since moving to the school. However she was admittedly rather bright and showed great potential, which Mrs Land and her fellow teachers all tried to encourage. That particular term however, Diana’s behaviour became troubling, leaning towards self-destructive even, and concern had grown as those around her began to fall into similar patterns.

She became increasingly disruptive in class, which was disappointing. The music teacher, Mr Allen, a very fine teacher, reported that Diana had shown real interest in a lesson about Vivaldi’s Four Seasons one day, seeming very alert to the ideas of repetition in Spring. Mr Allen said that other pupils had teased Diana about her quietly expressed keenness, and in response she had become so loud and totally unmanageable, ridiculing the music to everyone’s enjoyment and hilarity in her need for attention, that Mr Allen was sadly left with no choice but to send her out of the classroom into the corridor, from which she then disappeared entirely for some time. She had later reappeared, however, and – whilst unobserved by any peers – accepted to borrow a cassette tape from Mr Allen of the Four Seasons as performed by Nigel Kennedy. (Mrs Land and Mr Allen had then entered into a friendly disagreement about Vivaldi and whether as a composer he was altogether repetitive as Mrs Land held, or if in repetition there is created a particular kind of space for passionate and unpredictable variation, as Mr Allen contested).

The physics teacher, a stern fellow who always commanded excellent discipline, had informed Mrs Land that Diana, who was well-behaved and in fact usually rather studious in his class, had been sent out on more than one occasion having become suddenly unable to contain her energy, shouting out during demonstrations and the like. “She has become rather full of herself and thinks she’s the class comedian,” he said. “And I have moved her away from Asha T. and Kelly D., who conspire with her until all three of them are hysterical.”

In Mrs Land’s English class, Diana completely failed to submit her autobiography assignment without satisfactory explanation (tears are never a satisfactory explanation), and had to be taken aside one day for falling asleep in class, though she claimed she had only closed her eyes to better concentrate on Macbeth, from which Mrs Land was reading aloud.

Diana, until then, had really had no particularly strong and stable friendships, and had rather drifted on the periphery of various groups, observing from afar while never getting too attached, but she suddenly became much closer with Kelly, Jodie and the twins Asha and Mina. They were all fairly popular girls, though the boys seemed afraid of Asha and called Mina ‘Mee-nar’ and sang her name like fire engines over and over, as if they were still in junior school. They all lived a short walk from the school, like Diana.

The group began regularly disappearing at break times and lunchtimes into a puff of smoke behind the bushes near the long jump track, though they were never actually caught breaking any rules. Then their behaviour became a little odd; they were often seen huddled together, either some or all of them, speaking quietly and seriously to each other. They sometimes popped up out of nowhere, as if from behind a cloud, giving Mrs Land the willies; two straight-faced girls standing silently in a corner, or three girls sat where just a moment before there were no girls. Mrs Land once saw what looked like Jodie’s ponytail whip around a corner, but when she turned the corner herself there was no one there. Sometimes they didn’t seem to be anywhere, not that Mrs Land could track every pupil in school, but she found these absences somehow conspicuous, suspicious.

They kept up these disappearing tricks in class, too. Kelly and Jodie threw their French textbooks from a second storey window, claiming they had “fallen out”. The rather naive Mr Wiles allowed them both to leave the classroom to recover the books, and the girls did not reappear all lesson. Asha wandered out of Geography without permission and was found in the quad gazing into space, claiming she couldn’t remember what she was doing there. Mina seemed bent on disappearing her own work; she unpicked every stitch from a fine piece of tapestry she had been working on in Textiles, she put her very detailed drawing of an ant under the guillotine and sliced it in half (Lynn Gaunt of course tried to pass this off as artistic subversion or some such), and when asked to hand in a test paper by the History teacher, Mr Brown, she had stuffed the paper into her mouth and started to chew it.

Diana, meanwhile, screamed at Mr Donaghue when he asked her to remove a necklace, as the wearing of jewellery was against school policy. Diana refused to remove it and ended up in the Year 9 office again, where she still refused.

Diana screamed at Michael P., who said he hadn’t done anything.

Kelly was given detention for scratching graffiti about Michael into a desk.

Diana was given detention for scratching out graffiti about herself from a desk.

Asha was sent out of Physics for working the whole class into crude hysterics about the ‘bulges’ of water caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon.

Asha was sent out of Physics again, and then sent home and put on report, for holding the strap of Michael’s rucksack over a bunsen burner.

Jodie and Kelly became much too aggressive with some of the other girls during a rainy game of hockey and the match was stopped. (Gemma C. had to see the nurse.)

Mr Donaghue’s keys with the mini globe keyring went missing. Mr Brown’s spare glasses went missing. Michael P’s rucksack went missing. Mrs Land’s favourite dictionary disappeared. Mrs Land’s anniversary Parker Pen disappeared. In each case, a small white stone appeared in the missing item’s place, apart from Michael’s rucksack which reappeared in the quad, covered in disgusting blobs of chewed chewing gum. There was no evidence that the girls had anything to do with these missing items, but Mrs Land had a strong feeling that they might.

Diana wrote a horrible poem in Mrs Land’s English class.

During the assembly on role models, as the Head waxed lyrical about Working Together in a way that was quite flowery after all, Mrs Land slipped out of the hall for a few moments to seek out the apparently absent girls. She could have sworn that she heard voices coming from one of the girls’ bathrooms as she passed along a corridor, could have sworn she heard what sounded almost like chanting, but upon entering she found no one. Her eyes had swept steadily over the empty room; the doors of the silent cubicles all ajar, not a drip or a whisper from the lips of the taps, and the wastebasket holding no secrets, only scrunched up paper towels.

When the pupils filed out of the assembly a short while later, the five girls all appeared in line, each one making eye contact with Mrs Land.

Mrs Land discussed the issues with her fellow teachers and also with some of her best pupils from the choir, which Asha had stopped attending. Diana had been getting more attention from the boys it seemed since the summer holidays, particularly Michael. Mrs Land reluctantly recalled an awful rumour that some of the boys had been quite literally lining up to kiss Diana behind the sheds, that she had let them take it in turns one after the other. One pupil reported it was Diana’s idea too, not the boys’.

Mrs Land confronted Diana to ask if there was a problem between her and Michael, to which Diana only said that she wished Michael was dead. When Mrs Land pushed further, Diana had wished Mrs Land dead too. Mrs Land thought that wishing someone dead was about one of the worst things anybody could do, but it was when Diana screamed at Miss Gaunt that Mrs Land decided to call Joan, Diana’s guardian, in for a meeting.

*

It is difficult to say whether it was Joan or Miss Gaunt who had frustrated the purposes of that meeting the most.

Lynn Gaunt really did not have the ideal makeup for a teacher, did not have the powers of discipline nor the self-awareness and emotional distance required to handle a girl like Diana. Her deep, wobbly voice carried neither authority nor comfort. Her classes completely lacked any sense of order and she often appeared to be oblivious to the ruckus around her; she seemed in a world of her own. Lynn was a relentless optimist, which is admirable of course, but also a relentless do-gooder, and Mrs Land did not always welcome her interferences, in which she tended to make mountains out of molehills.

Lynn, quite a mountain herself, had tried to derail the meeting with Joan, turning the conversation towards the ‘quality’ and ‘promise’ of the work that had fallen from Diana’s folder. The focus of course, the whole point of the meeting, was to discuss Diana’s response when Lynn had taken her aside later and asked her about that work. Joan may well have mistaken the meeting for one of praise about Diana’s prodigious artistic talents, with Lynn honking on about her readiness for GCSE and even sixth-form exams, saying again and again in that dreary voice of hers “re-ally quite won-derful”, were it not for Mrs Land interrupting in order to quote Diana: you’re an F’ing meddling B who should mind her own F’ing business, which is what she had screamed at Lynn, also adding that she should watch her F’ing step.

Mrs Land had explained how often Diana’s behaviour had been unreasonable that term, how she’d been uncommunicative and uncooperative, bursting into tears at the drop of a hat, crying in the office about what was usually something very trivial, and now instead of crying she was getting into these rages and hanging around in her new little gang, and that she was quite likely a bad influence on other pupils Mrs Land was sorry to say, and Joan had become very vexed that she hadn’t been made aware of every little thing that had been going on which Mrs Land had calmly explained was quite impossible and that surely Joan would not thank the school if they were ringing her up every day with every minor hiccup or transgression.

*

It was the one that on all the posters bore the phrase Broadening Horizons. It seemed no one, pupil or teacher, had been looking in Mrs Land’s direction or at the pillar at the time, and so no one had seen exactly how it had happened, but later of course it was put down to the earthquake.

Two nights before the incident there had been a small earthquake, highly unusual for this part of the world. It had registered only 4.4 on the Richter scale but was powerful enough to wake almost everyone in the entire city, it being all anyone had talked about the next day, though it had beenlargely forgotten once another night had passed uneventfully. Still, that one day of earthquake gossip had been invigorating for the community, and people had eagerly shared with others in the street and over garden walls the strange dreams the earthquake seemed to have provoked and their thoughts upon waking, for instance Brenda the lollipop lady confessed to Mrs Land that she had woken in terror, believing a poltergeist was shaking her bed. Mrs Land herself had dreamed of a white cat whose four legs had suddenly started to shake and crumble.

The earthquake, it was later agreed, must have made some pretty serious cracks in the cement holding that particular orb on top of its column, and it must have been set wobbling somehow. Perhaps, people said, there had already been a fracture, a fault, and that it only needed the right conditions to send it rolling off, though whilst everyone remembered there being a hailstorm, no one recalled it being particularly windy, which added to the strangeness. It was agreed it was probably something to do with vibrations from below the ground, a mild and very localised aftershock for instance. There had to be some rational explanation of course, and what good did it do to keep talking about the how and the why anyway, when there was no one to blame for what had happened, not even the driver could be blamed; no one had seen exactly what had happened with the cement ball, but several people had seen – from several angles – what had happened with the car.

A sudden, loud hailstorm had struck just after the bell sounded for the end of the school day. The entire population of the school started streaming out of the double doors into the icy downpour, hopping down the steps and running down the slope in squealing, giggling clusters, the black shoulders of their coats turning white, hailstones bouncing off umbrellas, bouncing off the tarmac, some pupils pausing to see who could catch the biggest one in their palm, but all moving quickly down towards the school gates. Mrs Land was stood by the steps, hail thudding onto her grey umbrella, when the umbrella was knocked roughly aside and out of her hand and the cement boulder, bigger and heavier than a washing machine, appeared for a fraction of second where her umbrella had been, as the enormous thing flew past her face and dropped to the floor with a startling smack. She was alert enough to flinch aside, or it would have crushed her shoulder, or smashed every bone of her foot. Then off it went, rolling down the slope after the running pupils, its rumble inaudible beneath the white noise of the hail and the thrilled shouts and laughter. Mrs Land shelved her shock and started to run too, to shout, shouting at the pupils to move, move quickly, shouting the names of individuals she could make out. Miss Gaunt had appeared and joined in, her shout like a distressed llama, and Mr Brown the History teacher shouted louder than both of them, and pupils began leaping out of the ball’s path as it picked up speed, and Mrs Land could just about make out its grating sound like a boulder being rolled away from a mysterious cave entrance, and the three soaking teachers were still running after it and yelling and waving their arms, and pupils were pointing from afar, screaming and shouting to each other, shouting each other’s names, the ball rolling along at a fair pace then, and nothing it seemed, about to slow or stop it, rolling right through the school gates and towards the road, all the shouting and screaming rippling along behind it, each group of kids warning the next, and Michael with no hood on and his whole head a happy wet mess about to cross the road turning and seeing the ball rolling towards him, towards the road, and turning fully around to face it with open hands as if to stop it in its tracks, and Aaron W. shouting his name and pulling Michael by the arm and Michael being flung into the road and the driver seeing the huge cement ball rolling onto the road but not seeing Michael who had been swung around a little too hard by Aaron and was on a simple trajectory now into the path of the car.

Even over the noise of the storm, many heard the thump, the soft kind of crunch.

Brenda the lollipop lady screamed.

The ball, oblivious to the fuss, continued across the road in a serendipitous gap in the traffic, bounced against the curb on the other side, then slowed and rolled along the curb, following the corner until it came to rest quite gently against the back of a parked silver Volvo. The storm subsided, then stopped. Because of all the excitement, with the ambulance and whatnot, it was a while before anyone noticed that Diana had disappeared.

Remains

Diana’s artwork, which Miss Gaunt had found, and which had subsequently been ripped and thrown into the bin by Diana during the confrontation in the classroom, and the bin kicked over, had afterwards been recovered in secret by Miss Gaunt, who took it home with her where she had attempted to repair it with sellotape.

*

The work was made of three sheets of A4 paper which had been folded together in the style of a book. The papers had not been fastened together in any way, but had been ripped in large pieces so that the order of the pages in most places had not been disturbed. The outer sheet, which formed the cover of the work, was decorated in a reasonably regular pattern; small stars had been drawn by hand with a fine tip gel ink, gold. They were the simple kind of stars that are made of four short interlocking lines, not the kind of star made of five sides drawn in a continuous fashion without removing the pen from the paper, nor the kind where two triangles are overlaid, each facing the opposite direction, nor any other kind of star. Each star was on average half a centimetre in diameter and the stars were generally placed around two centimetres apart. The pattern was drawn on both the front and back cover; there were approximately two hundred and thirty stars. On the back cover the pattern was broken in the bottom left corner where several vertical pencil lines of varying thickness had been drawn in imitation of a barcode. The inside of the covers, both at the back and the front, were left blank except for the initials DM in the bottom right corner of the inside back cover, written lightly in pencil at a height of one centimetre.

The eight pages created by the folded paper within these covers were illustrated with sixteen small drawings, two on each page, each one in landscape with a corresponding rectangular border drawn around it. The borders were very straight; it is highly likely that a ruler had been used. The borders appeared to have been drawn before the illustrations themselves, perhaps lightly, and then redrawn with thicker lines following the completion of the contained image; this could be inferred from the way that some of the drawings appeared to have run out of space, as though the drawings had been less easily contained in each space as the illustrator had hitherto imagined, likely evidence of poor preparation, overconfidence or a lack of patience. As a result of this approach, some of the subjects or details were slightly distorted, or items were missing that would perhaps have been included in the illustrator’s original imagining.

With the exception of the gold stars on the cover of the work, there was no colour besides the grey of the pencil. It would appear that more than one thickness of pencil was employed, likely a 4B for the borders and a 2B for the illustrations.

Of the sixteen drawings, twelve of them contained human figures. A figure recognisable as the same girl appears in all twelve of those drawings, usually with other figures but in two cases drawn alone. In half of the drawings of the girl, though she is still recognisable as the same girl, she is drawn, quite convincingly, in negative; her hair is white and her facial features stand out brightly from the shaded skin area. The girl is nearly always smiling. The other figures are not always smiling.

Five of the drawings contained animals: three cats, one monkey, one giraffe. Of the cats, one was white, one was black (grey) and one was white with dark patches. None of the cats were fully visible within the borders, each one either missing a tail, a paw, an ear. One of the cats had only one eye. The drawing of the giraffe, which was very detailed, was accompanied by two small figures visible in the background behind a fence, a woman and the girl; both human figures were presented in negative. The monkey was drawn sitting beside the girl with each drinking from a glass through a straw. The girl was not shown smiling in this picture owing to her action of drinking through a straw.

The drawings themselves, despite the rips and smudges and the yellowing distortion of the sellotape in various places, showed skill insofar as they were good likenesses of animals and humans – though it was not possible to be sure if the human likenesses were good likenesses of actual people they were meant to represent – and insofar as they were reasonably well composed aside from where they had run out of space as previously mentioned with some parts of the likely intended image distorted or missing in a manner that is uncharacteristic of photography, if the intention was that each image was meant to resemble an actual photograph, whether copied from a real photograph, drawn from the memory of a real photograph, or imagined entirely.

*

On the day of the confrontation in the classroom, Diana had returned later, when the room was deserted, and looked into the empty bin.

Part Three: More Than This

Backspin

Talk, in three places

The talk in the newsagents was usually brief, depending on the number of customers and whether it was Les or Teresa working. It was sometimes confined to a single comment bad business up at the school or a joke any of your balls fallen off lately? the latter directed to Les, rather than Teresa. A customer might overhear the tail end of a more in-depth conversation between Teresa and one of the regulars well they said she’s run off before and then the conspiring tone would switch swiftly to a spritely well anyway, yes Tess, I’d better get on, can’t stand round here yapping all day…

Next door in the shiny surroundings of Hairways, the talk came in bursts between the roar of hairdryers, punctuated by the same old questions of length and style. My friend’s lad in the year above…yes about there…my friend’s lad…no, a bit more…my friend’s…yes, that looks right…just a water please, love…so, my friend’s son is in the year above and he wasn’t in school that day because they were all on a trip, but he said there’s been funny business up at that school lately…yes, yes…he told my friend there’s something weird going on, definitely…why, what did you hear? Oh really? Oh thanks, love. Right. Well. Well Lee, my friend’s lad, says things keep disappearing. And girls. No, not like that. I don’t know, some kind of mischief. That one of Joan’s especially, you know, the miserable looking one…oh yes she is pretty but… I don’t know, sad, don’t you think, anyway she might have something to do with it…what’s that? No not the earthquake, the mischief, though the way people are talking about her maybe…no, yes that is ridiculous, yes, but who’s to say the earthquake was what happened to that big great ball anyway, that’s what they’re saying but it’s weird if you ask me, great big thing like that just falling off, earthquake or no…yes, that’s what I said. Weird. Well that girl, she didn’t get on with that lad by all accounts, that’s what Lee says, my friend’s lad, and he says how her and some other girls had been up to no good, and how that girl, Joan’s girl I mean, how she’s gone a bit wild. You what, love? Drugs? Drugs, eh! Well yes, you might be right, if she’s acting one way and then another, you might be right. But what about that poor lad? He’ll be alright they said, out of hospital soon, few weeks at home, he’ll be right. That teacher, Land, stick up her arse, oh yes she’s been there since I were a girl at that school, she’s been telling anyone who’ll listen how she could have died, it could have brained her. Oh yes, life flashing before her eyes, all of it. If I was just an inch to the left, she says. Or right, whatever. I mean all the kids hate her but no one’s ever tried to kill her. But Jennifer, my neighbour, her husband swore he saw one of those girls running down our street in the middle of the night in nothing but her nightie, and more than once, I mean what on earth are they up to, and if it’s not drugs it’s the other if you ask me, they said Joan’s girl’s been putting it about rather a lot if you know what I mean, they used to call her Princess and now they call her much worse things instead. You what, love? Yes.

Slag.

You have to be careful what you say of course. I mean you didn’t hear that from me. That Joan’s got a lot of friends hasn’t she. Like a gang themselves, her and those Sharons. And those two girls, the sisters, everyone knows their dad. I wouldn’t want to get on his bad side, would you? Yes, that feels much better, thanks so much, love.

Across the road in the small doctors’ surgery, the waiting room was overheated and filled with the incessant low buzz of the local commercial radio station. The telephone kept ringing and the receptionist kept answering, but those waiting were silent as satellites, until the intercom cleared its throat and called a name, and each time a patient would leap from their seat as if chosen on some dark version of The Price is Right, and go hurrying and shuffling deeper into the building to knock on a numbered door, waiting like a schoolkid for the authoritative voice on the other side of the wood to grant them permission to enter, sitting down and not speaking until spoken to, until asked “what can I help you with?” or “how are we doing today, then?” or a simple “so then”, before their lips began tentatively to move, releasing the embarrassing, unbelievable confessions that came slipping and slobbering off their tongues:

I’m vibrating. On the inside. But only when it’s waxing.

It has always given me migraines, but now my migraines are like earthquakes.

I can’t sleep. Everyone knows it stops you sleeping.

It’s brought on the menopause.

It explains all the missing cats.

I know that’s what it is because the earthquake told me.

There’s something wrong. Not just with me. With everyone. With everywhere.

I can hear it crying at night.

It must have taken that girl.

Joan, in Orbit

Five days after the accident, and a whole week since the night of the earthquake, as the people of the star-shaped suburb once again lay sleeping in their various positions in their beds, a high wind blew across the whole county. In the morning, a jogging Joan had to dodge several felled and gawping wheelie bins in her path as she bobbed along the pavement. Before she had reached the bottom of the street she saw strewn on the ground: a fake pearl necklace, a plastic thermometer, an inhaler, an empty and battered KFC bucket, a number of washing up liquid bottles and plastic milk cartons, a roll-on deodorant, rizla packets, fag packets, medicine packets, parts of a smashed wine bottle still held together by the label, and she overtook a pair of black tights that had landed across a hedge so that they appeared to be running, too. All in all, it looked like the neighbourhood had been sick.

Jogging was not fashionable and Joan, on her irregular trip once around the block, was the only person on the street that morning who was moving at any sort of pace, the only people she passed on the downhill stretch being the unhurried postman who nodded hello, and Brenda the lollipop lady who waved her free hand, the one not holding the huge lollipop, before going into her house. Joan bounced along on her cushioned soles, a white cap keeping the winter sun from her eyes and preventing her hair from flicking into her mouth, as well as providing some small cover for the embarrassment she occasionally felt but fought against. Her fists pumped weakly by her sides and her flesh wobbled, especially around her middle. She tried to keep her breathing steady as the air shushed past her ears, tried to keep her focus on her feet as they tap-tapped their rhythm on the pavement.

Joan thought very highly of her feet, despite them being the lowest point of her body. She had long believed in the wisdom of feet, that they kept secrets in their bellies, and she was a fan of reflexology, to which she had that hippy teacher from Diana’s school to thank for introducing her. When Joan went for her occasional jog, if she was able to really give herself up to the rhythm, she found she could let her feet take over from her thinking mind. It became as though her feet were talking, and, once her brain took a step back, Joan could just listen.

Perhaps the neighbourhood does get sick sometimes, her feet were thinking now as they connected and disconnected from the pavement. Perhaps it does get sick, and then gets better again, just like a person. Depends on the sickness, Joan’s brain, not yet at bay, answered. Joan’s brain tried to picture all the actual viruses that were likely to be circulating at that point in the year, as everyone turned to face Christmas again. She envisioned germs like little asteroids shooting from noses and roaring unseen through the air. Her feet liked this idea and ran with it. Asteroids, yes, they said. Shooting towards their victims, victims like planets, planets orbiting around the neighbourhood, their own little solar system. Just like you, now.

By the time she turned the corner at the bottom of the street, Joan was registering the wind’s debris only as obstacles rather than items. She did not look across the road to see if the shops had been blown away, or at the Green to see if anything new had been caught in the fingers of its few bare trees (only the day before she had noticed a deflated but still shiny heart-shaped balloon tangled in a high branch). She barely looked up from the path ahead of her. She only listened, as the movement of her feet, her body, began to put everything within into better order, her muscles and nerves becoming chains and mechanisms in some obscurely-purposed factory, her thoughts winding around as if on a spinning reel, her mind being tidied as she moved forwards.

Joan’s feet, still pondering asteroids and solar systems, were wondering what would represent the sun if their little corner of the world really was a sort of solar system, but after dismissing various elements of their immediate and familiar surroundings Joan’s brain and feet both agreed it was a bad analogy altogether. A neighbourhood, the feet thought as they travelled up and down the subtle hills and troughs of the asphalt, is more difficult to describe than the city of which it is a part.Cities brand themselves, Joan’s brain piped back up in agreement. Give themselves identities: this is what we do here, this is what we like to eat, these are our landmarks, our successful people. A neighbourhood is more often defined by its value: its house prices and crime rates. What kind of warped view is that?

Joan’s toes turned left again at the next corner, and the rest of Joan followed them onto the street that ran back uphill, almost parallel with their own street, only the houses were slightly nicer here, and somehow it had accrued less windblown litter. Joan, looking up, saw the sun had reached only the top halves of the houses, while the bottom halves were in shadow. Her cap cast a similar shadow, only on the top half of her face.

A family, her feet were pondering, shouldn’t be like a solar system either. Why should everything revolve around one sun? A sun can die just like anything else, Joan’s brain offered. That’s how you get supernovas. Black holes. Joan remembered this stuff from school. The unlit, top half of her face contracted into a frown. They always teach optimism at school don’t they, so that kids leave with the impression that the world’ll keep getting better. Do they think kids won’t notice the black holes everywhere?

Not that Joan was a pessimist. Quite the opposite; her feet said. She was doing herself a disservice. She was angry that’s all, angry with the school, and the black holes they called teachers who couldn’t see past the end of their rulers. No, she didn’t mean that either, Joan’s feet told her, it was frustration, that’s all, and that’s fair enough given everything that had been going on. It was fair enough to be frustrated.

It wasn’t deliberate, surely, any of it.

Anyway, girls have every right to disappear now and again. Especially a girl like Diana. They usually reappear, after a while.

Joan jogged past the house of one friend, and then another. The windows were dark and no friendly faces appeared, but Joan smiled as if they had, thinking of how they laughed about her jogging, running about in the streets for all to see. They preferred their exercise bikes, or the occasional aerobics class, each to their own. Joan felt grateful to have them so near, to be separated from them by only a thin line of the planet. You might not choose your family, or your neighbours, but sometimes you end up with friends who are both.

How often we are looking through the wrong end of a telescope.

Joan jogged passed the house of the twins, a big house with a white gravel path and ridiculous stone lions on either side of the gate. One of the twins, Asha, had been at Joan and Diana’s house a few weekends previously, seemed like an OK girl really, a bit rude, a bit snobby at first, Joan had seen it on her face when she came into the living room, but she was fine once she settled down, and they had gone up to Diana’s room with the cat and some snacks.

That Friday, after the ‘incident’, as people were calling it, Joan had repaid the visit. She had opened that gate and crunched up that path and knocked on the door. The twins’ father opened it; he had been cold towards Joan. She only found out then, as she stood there coatless on the doorstep, that Asha and Mina had been forbidden from seeing Diana outside of school any more, and their father said, though not in so many words, that Diana was a bad influence on his precious snobby daughters, said they’d been having nightmares, that Asha had woken up in the night stood by her sister’s bed with a pair of scissors in her hand, though whatever he thought that had to do with Diana Joan had no chuffing idea. The father had called Asha to the doorstep and, pressed by him, she had confessed to Joan that she had tried to set Michael’s rucksack on fire in Science because he had threatened her when she told him to leave Diana alone. Her father threw his arms up in the air as if this proved something to Joan, and talked over his daughter, who was trying to tell Joan how Michael had been following Diana home from school every day.

Michael, that little asteroid.

With her father’s permission, Asha had given Joan the telephone numbers of Diana’s other friends, yes friends, not gang members as that teacher would probably have it, no, not the hippy, the old, short one, the wicked witch who was almost run over by the ball, which she had implied was Diana’s fault when Joan came looking for Diana after she didn’t appear at home, as if Diana could push a boulder off a bloody pedestal, and anyway Joan would have to tell Diana to try dropping a house on the damn woman next time, that damn woman who dared tell Diana last week that her handwriting was ‘promiscuous’ and ‘showy’ because it had started sloping too far to the right and Diana had come home in tears.

She’d got the numbers anyway, and called Jodie’s house, but her mother said Jodie wasn’t there, was probably down at the shops, and oh how those girls Jodie and Kelly had swung between embarrassed and sassy and back to embarrassed in front of those boys when Diana’s guardian had found them at the playground, come right up to them, caught them in the half-dark putting out their cigarettes, started asking questions while the boys stood around spitting on the floor. One of the girls had started to swing and took off toward the sky but came back down with gravity and Joan’s question, and it turned out that they weren’t allowed to see Diana any more either.

Joan, on this bright morning on the parallel street, realised she was not doing very well at surrendering to her feet this time. There were too many thoughts today to be tidied up neatly. Nor had Joan yet realised that the regularity of exercise would improve her fitness, and that a short jog once a week, usually less depending on her mood, would not significantly improve her lung capacity or general stamina, and suffering a mild palpitation as she reached the corner, she paused, leaning with one hand atop someone’s garden wall. Joan’s feet fell silent.

Above the sound of her breath and the pulse beating in her ears, she heard the rasp of a plane and tilted her face up at the bright sky, her free hand lifted to the brim of her cap, but instead of a plane she saw the Moon, or most of it anyway, looking back at her with its great eye. What was it still doing up at this time? Joan, who had been avoiding an eye test for years, squinted at it; it was difficult to see any details, any of the shadows on its surface like patches on a cow, but she knew they were there. Even if her little eyes could manage to adjust, if she could make out any features of the Moon’s face, they wouldn’t stick if she looked away. All that would be left in her mind’s eye would be a vague shape, and that might not even be accurate, and she might look again and see that she had misremembered how full the Moon was, up there in the morning sky.

At that moment, there at the top of the hill, Joan thought that the Moon, staring back at her, looked like it wanted to come rolling down, but she guessed the Moon knew how much that would hurt. Joan’s heart rate had slowed, but her feet seemed stuck to the floor. She stayed by the wall, looking down now at a flattened circle of chewing gum beside her running shoe. Hadn’t she read, or seen on TV somewhere, about how the Moon keeps things stable, the tides, the seasons, all that, but that in fact it is moving gradually further and further away from us? Still, it must be a natural thing, thought Joan. And even the Moon has to grow up someday.

She remembered, without the help of her feet, the time the social worker had said that Joan should always be Diana’s ‘rock’. And how Joan had promised herself, herself only, that she would do her best to love Diana from the distance that Diana allowed.

Joan took another squint at the Moon. She thought it must love the Earth very much. Hadn’t the Moon once been a part of Earth? Wasn’t it just made of our fragments? She wondered what the Moon thought of people. She wondered what the Earth thought of them too, if it loved them even though they didn’t seem to be very good at taking care of it.

Joan had rested her hand close to an abandoned spider web which had gathered nothing but fluff; perhaps the spider had deliberately caught fluff, with the intention of making a jumper in the winter. The thought tickled Joan enough to unstick her feet from the pavement, allowing her to continue on her orbit.

She ran along the top road for a short stretch. There was the school. From this part of the street, Joan could not see the missing boulder. She smiled to herself, realising she couldn’t see a missing boulder if she was stood right in front of it. She did not know what they had done with the great big stupid thing. Whether it would be replaced, or reappear one day, back on its column. A decapitation undone. Or if it had been destroyed, like they do sometimes with dangerous dogs.

Joan turned left once more, back onto their familiar street and its mild downhill slant. Ahead of her, someone was hoisting a wheelie bin back to its upright position. Joan straightened her back, dropped her shoulders, held her head a little higher.

Winter sun painted pleasing colours all around her, and Joan felt a sudden longing for summer, but did not know if it was a past summer she longed for or a future one. Joan had not been able to stop wondering how it was with Diana’s drawings, the photo album, and whether Diana was trying to capture the past or change it, or neither.

Joan’s feet, though quiet, were thinking of the spaces between the stars. Of holes. Of craters.

Joan gave a small wave to a neighbour who was taking a sweeping brush to the litter around his gate; what looked like the contents of a hoover’s stomach, all hair and fluff and dust blown by the wind into the wires of the gate hinges. Looking at it made Joan feel dusty, and she shuddered.

The dust that settles on people can be hard to shake off, whispered Joan’s feet. Often they don’t know it’s there. And those who do know don’t always want to shake it off, at least not completely, not til they know what they might find underneath it all.

Joan had needed to make those visits, and ask those questions, on that Friday evening. But she had known already how to find Diana, or at least how to let Diana find her own way back. She knew that problems sometimes needed a little space and time, that sometimes it was necessary, irresistible in fact, to orbit the problem; revolution often tended to present a resolution of sorts. And even when that resolution didn’t seem to make much difference on the surface, something important had usually been learned on some level.

Diana had reappeared over that weekend, piece by piece, word by word, becoming more solid by the hour. When she materialised on the sofa on Sunday night, Joan noticed that she had taken off the sharktooth-looking necklace that she’d bought herself in that goth shop in town and had been wearing like a medal for weeks. Her face was unchanged, the sad sweet face that Joan loved. Every freckle and blemish was right where it had been before.

Joan had let Diana take a couple of days off school the following week. They watched Trisha and ate Jaffa Cakes. Diana had talked about her grandmother, how she’d told Diana that her eyes were moons, and that she wasn’t really blind; she could see everything.

Jogging Joan approached the little house she shared with Diana. The cat was waiting on the wall, watching with apparently no interest in what Joan might be running from or surprise at her having been gone. That cat had always been Diana’s best friend, Joan had heard Diana telling it so. The two of them shared a love of curling up in corners, and both delighted in finding a warm stripe of sunlight across a room. People often assume the worst about cats, don’t they, if they aren’t cat people. They think all cats are lazy and selfish. Though as Joan reached the gate, panting and her chest burning, the cat did look lazy and selfish, truth be told.

Pausing at the gate under the indifferent gaze of the cat, Joan looked away down the street again, considering another go around. Maybe if she did another loop she might start to let go, and her feet might speak up some more. But no, forget it. Some days were just harder than others.

Inside, the kitchen clock was ticking and Diana sat at the table, turning the pages of a magazine. She looked up and rolled her eyes at Joan’s red face.

That night, Diana and Joan danced around the living room and the kitchen, spinning around until they fell down laughing, both their faces flushed pink.

Kitty

Dream about a cat (bad)

Come, Kitty

Kitty comes. Fur white.

Where have you been tonight?

Kitty squints and purrs. The secret hers.

What did you bring for me, Kitty?

She rolls onto her back. Don’t tease!

Kitty, please, where is my present?

She flips me a paw with too many a claw

You brought me the Moon, you’re smuggling a crescent!

I pinch it, thin blade, between finger and thumb

Sharp-smooth, opalescent. Hooked in, it won’t come

Kitty, don’t howl! Kitty, don’t tease!

I draw out the Moon

and Kitty bleeds

Diana Morement, Yr 9